An End to Summer

Alone in the Med might be worse than in a crowded trench on the front line

I stayed too long, and one day I looked up, and summer was no longer there. They say it’s the little things, but they seemed pretty big to me. It was quieter, for a start, but the waves rolled in louder. In fact they crashed onto the beach, in a desperate, lonely kind of way. As for the tourists, they were long gone; every single one, and not only them, either. My favourite barmaid, who knew which glass of red wine I liked for breakfast, along with my espresso, and where I liked to sit at the bar, well, she was gone too, pehaps back to the village, where she looked after her grandmother, she mentioned, once, pouring me a top up in my wine glass. The village was in some mysterious location over the horizon, and the horizon was a mountain behind the city, straight out of central casting; a wonderful decor always present as a backdrop, and in sutumn tinged almost purple at sunset.

Perhaps one day, I fancied, I would climb it, like I used to when I was young, not even thinking about such matters but just doing them.

But I guess the just doing without thought is what got me to recuperate at the town by the sea, now thinking and not doing. That is probably one of the differences of being in a war, and not. The other is being alone, because you are never solitary during war. Nobody is, and everyone is looking out for each other. or getting killed, of course.

Things like that make the disappearance of my barmaid a little harder to bear. In Ukraine when people disappeared, they tended not to come back. I guess the barmaid would not come back till next summer. And next summer I will more likely than not be in eastern Ukraine again. Until then I didn’t much enjoy the peace too much; everything was closed, and there was only me facing the crashing waves at the beach, and I had too much on my mind to try to climb the mountain behind the city.

Once you’ve spent a winter on the trenches, at war against a brutal enemy who have no right to be there, the only option you have is to go back. What else could you do that has as much purpose? And how is it possible to sit on a luxurious sofa again when you have been able to handle the gnawing cold of the bunker, a dug out within a trench that is either full of thick mud or frozen to the depths of experience: in that first year of war no-one was rotated. There was no leave. The best of the very best volunteered for the front and were dumped there, for months on end and forgotten. Now and then weapons arrived, from frivolous friends in NATO, who in those days were so afraid of Putin they were sending less than the bare minimum, and the bare minimum in those early months of the war was a low barrier: Germany had donated a few thousand helmets for goodness sake. Helmets!

The food available in early spring 2022 on the front line was one potato a day for a while, and officers who stated so to a media outlet were arrested for possible desertion — after all, instead of being interviewed in an unknown location they could have been sinking in trench mud. I mention that now, because Ukraine has come a long way, and still exists, as it must, and deserves to. But I valued potatoes more than any of the excellent tapas I sat alone eating with my morning wine in my enforced recuperation.

Outside Ukraine, it is different. When one reads the many excellent reports, essays, articles written far from the war, there are recurrent themes that have become almost a currency they are so recognisable. Perhaps one used most often is meatgrinder, to describe Russian tactics of throwing man and machine forward in waves. Further description almost always points out what a waste of life this is, as well as equipment, and to this some mention a salient fact; that Russian vehicles are built quickly, cheaply and in large numbers, without any great expectation they will last as long as the expensively-made western and Korean models.

But outside Ukraine there is next to no focus on any discussion following the meatgrinder assertion: I have not seen one piece describe what the effects of this tactic has on Ukrainian troops, other than one or two about morale when the term was first in use in the battle for Bakhmut, but a few words on morale barely scrapes the surface.

Many may speculate how poor, and inefficient the Russian military is. True. But that does not change the fact that facing such destructive tactics is very difficult. The Russian army going forward is ruthless, and NATO spokespersons may smirk at times, and point out how ineffective Russian tactics are, but they have never faced them: it’s dirty and difficult warfare, and one of the reasons Russian attacks are not efficient is because Ukrainian defences are so well-organised, despite the more oft than not snide sniping from too many western commentators, happily outlining supposed shortcomings in Ukrainian high command. In fact one questions sometimes why so little is said about the Ukrainian military, other than discussing tactics: there is a lot about how bad the Russian troops are, and almost nothing about one of the reasons they are so bad; because of those who they are facing.

When Hitler’s forces attacked Czechoslovakia in 1938 the Czechs surrendered in days. So did the Belgians, a little later, and the Dutch. The Danes and Norwegians fared little better, and it was from the Poles that we saw bravery. The rest we won’t mention, because they were just a little too pally with Hitler, aside from the Serbs and of course the Brits. But how are we going to expect European countries that capitulated so quickly, or joined the Nazis to really support Ukraine, which is fighting so hard to hold onto their land? The answer is almost self-evident. What if Czechoslovakia had held on for a bit, in 1938? After all, the country was a leading arms. supplier then, and requests for more weapons to GB and France could not have gone unanswered. Could that have stopped WWII? Possibly.

That knowledge ought to put Ukrainians’ determination to defend their land in new light, because commentaries about the bravery of Ukrainians is almost fetishtic, and not necessarily admired, and generally not given the value and consideration deserved. Only the Poles seem to get it, and they are the only country in Europe who actually block social payments to male Ukrainian refugees, who by Ukrainian law should be in their country. The rest of Europe actually rewards Ukrainian men who have fled the war. So much for admiring bravery. But this needs highlighting again and again, only it is not.

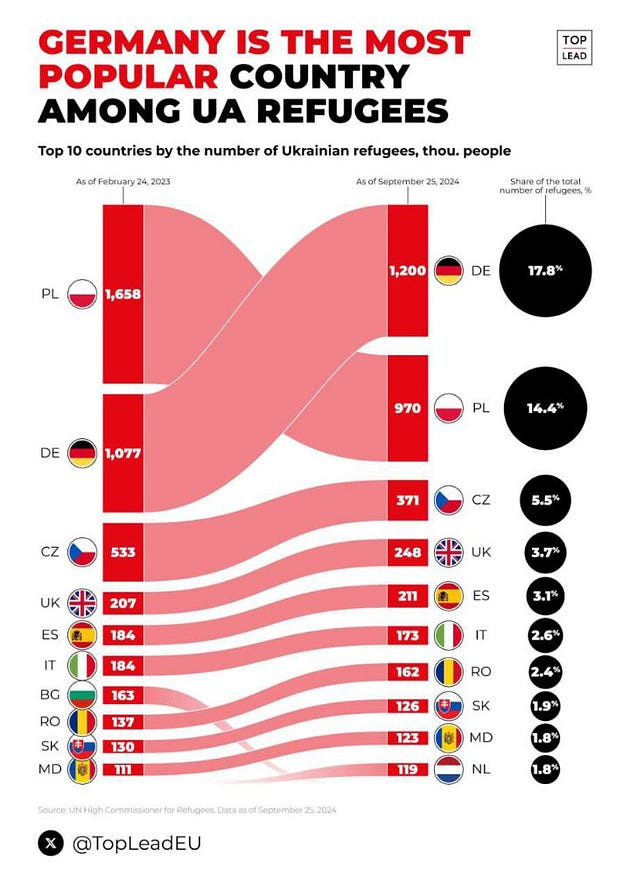

Speaking of refugees, the chart below gives an interesting perspective:

We need to be careful. The war has given rise to a fair amount of analysis, some war gaming, and some effors at explaining why some things might be happening as they are. One would imagine that this hones critical thinking. It doesn’t. In fact as support does not waver, indeed solidifies, much commentary is tamed by bias, so that basically what Ukraine does is good. How can you blame anyone? Giving Ukraine a hard time right now seems just below the belt.

But inside Ukraine lives depend on good decisions and action. Outside, commentary is catching up with the sudden incursion into Kursk, and much of it has settled into praise, outlining why it was so brilliant, and clever.

There is more questioning inside Ukraine, esèecially in the East. Was the incursion into Kursk worth it?

Obviously one of the intentions of this dramatic action was to detract from Donbass, and prove Ukraine was capable of launching an offensive.

It might distract Russian units away from key objectives. It would prove to Americans in the middle of a critical election race that Ukraine was worth supporting, it would seize land to use as a bargaining chip in new secret negotiations due to start in a couple of days, intended to end the long range strategic war against power grids and refineries.

So it was a win-win?

In days resources were taken from key areas of the front and joined with rested troops that were supposed to rotate into the frontline on the East. Nobody could know. Not even the leaky Pentagon. As the lightning strike quickly grabbed everyone’s attention the first thing that went out of the window was the so-called peace talks in Qatar. The Russians immediately refused to attend. Foreign Minister Kuleba, like almost everyone else, knew nothing about the operation because if he had he might have told the president it would kill any hope of an agreement. An agreement seen as critical for Ukraine as winter approaches, but dead since then Russia launched its largest ever missile attack on the energy system, and continues to take ridiculous risks targeting nuclear power stations.

The Ukrainian army did its job, ripping in to Kursk and sending Russians fleeing. As an unfolding story it grabbed the headlines and morale soared nation and army wide. But as time went on the questions have become the strategic objectives were what?

It was an offensive to change the war the first commentators from outside Ukraine announced — but nefore long it had gone from some grand campaign to change the war to an annoying incursion little more than an effort to take land for peace negotiation leverage.

That’s it? That’s what it was for?

The Russians realised quickly that was all a distraction ploy and they weren’t playing ball. Let them get on with it, not worth doing much about despite the fact it made Russia look stupid and foolish, was their view. Putin and his henchmen did not need that land, it’s a pin prick, valueless, what could the Ukrainians do? Even if they reached Kursk they could never take it. Russia did what it always does — throw some sacrificial troops in to slow things down and wait for more to stem the tide. And that’s exactly what they appear to have done, in their own clumsy and disjointed way.

But I remain worried the fast mobile forces Ukraine uses are not strong enough to break a brigade of battle familiar troops in defences. The more land the Ukrainians take the more men they need to keep it. Already they’re digging in and preparing to defend the fields and small villages they captured with such fanfare. Because now the real battle begins. They have to defend all this territory of so little value, that has no strategic significance of any kind. Because plans devised for dramatic effect rather than military objective are hollow. And that is exactly why this whole thing was a possinly a strategic blunder.

From inside Ukraine I might now say we must either withdraw to save the cost of defending something worth nothing, or commit the ultimate military mistake of protecting something of zero value and wasting valuable men and machines and resources holding it.Forget the international audience. They don’t really care. I do though, because inside Ukraine one meets the wonderful Ukrainians going into battle, and fighting for their country. Sometimes, I feel articles from outside Ukraine about the conflict forget this.

So I might say all that, but only might, because from inside Russia it is much easier to contact the Russian partisan units who detest the Putin regime. It is easier for Ukrainian special forces, like Atesh, or Shamans to go deep into Russia and hurt the Russians where they deserve to be hurt.